Interfaces & Data Structures#

Using “Lecture 2: Data Structures and Dynamic Arrays” from the course “Introduction to Algorithms” [DKS20] as inspiration, let’s analyze the difference between an interface and a data structure.

Interface |

Data Structure |

|---|---|

- Specification |

- Representation |

Main Interfaces: |

Main Data Structure Approaches: |

Sequence Interface#

In summary, a sequence is a collection of ordered objects. Example: \( (x_0, x_1, x_2, \cdots, x_{n-1}) \). It’s important to note that order is extrinsic. Some special cases of sequences include: Stack and Queue.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) Extrinsic order in an ordered collection refers to the characteristic where the sequence and arrangement of elements are explicitly defined and maintained by the data structure itself or by operations performed on it. This means that the order of elements is not inherent to the elements themselves but is imposed externally.

Sequences differ from sets in that elements have positions within the sequence. And the following operations are supported:

Initialization (with a constructor)

Adding an element at a given position or at the end of the sequence

Removing an element at a given position or at the end of the sequence

Identifying the position of a given element of the sequence

Checking whether the sequence is empty

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) Sequences do not necessarily implement order of the items attributes. That is, take the object (1)

<a, b, c>and (2)<c, a, b>they are both sequences even though object (2) is not ordered. When it comes to the item’s attributes, the difference is that the object is placed between two other objects. In other words, where the object is located matters.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) Sequences are like book shelves (even though the books may not be organized by alphabetical order, the order they’re located in the shelf inevitably matters).

Set Interface#

In summary, a set is a collection of objects not necessarily in order. Sequence’s about extrinsic order, set is about intrinsic order.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) Intrinsic order doesn’t necessarily imply any specific sorting or organization; it’s simply the way data is initially arranged in a Data Structure.

Sets support (at least) the following operations:

Initialization (with a constructor)

Adding an element to the set if it’s not already there (no duplicates)

Removing an element from the set

Checking whether a given item is in the set

Checking whether the set is empty

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) A set has weaker requirements than sequences and therefore has more implementation alternatives.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) The order of an element in a set doesn’t matter by itself. But the interpretation of where the item is located that matters.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) Sets are like drawers (the order doesn’t matter when picking up an element).

Array Sequence#

Arrays excel in static operations but are less efficient in dynamic scenarios. When inserting or removing items, arrays require reallocating memory and shifting all subsequent items. This process can be computationally expensive, especially with large arrays or frequent modifications.

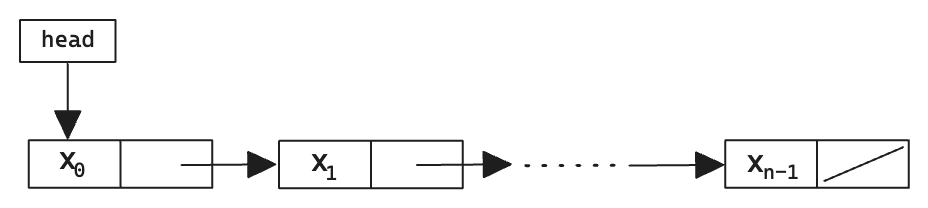

Linked List Sequence#

A pointer-based data structure where each item is stored in a node that contains a pointer to the next node in sequence. Each node consists of two fields: node.item and node.next. Manipulating nodes is straightforward as it involves relinking pointers. The structure maintains a pointer to the first node in the sequence (head). The figure below shows an example of a linked list.

Fig. 2 Linked list schematic.#

Dynamic Array Sequence#

In Python, a “list” is implemented as a dynamic array. To optimize dynamic operations at the end of the array, an efficient strategy involves allocating extra space to prevent frequent reallocations. This strategy maintains a fill ratio \( 0 \leq r \leq 1 \), representing the ratio of items to allocated space. When the array reaches full capacity (i.e., \( r = 1 \)), additional space, typically \( \Theta(n) \) where \( n \) is the current size, is allocated at the end to maintain a specified fill ratio, such as 1/2.

Notably, a single operation may require \( \Theta(n) \) time for reallocation. However, over any sequence of \( \Theta(n) \) operations, the average time per operation becomes \( \Theta(1) \). This balancing ensures efficient performance across dynamic operations on average. Take a look at section Amortized Analysis about amortized analysis.

Data Structure |

Container |

Static |

Dynamic |

|---|---|---|---|

Array |

\(n\) |

\(1\) |

\(n\) |

Linked List |

\(n\) |

\(n\) |

\(1\) |

Dynamic Array |

\(n\) |

\(1\) |

\(1\) (amortized) |

Amortized Analysis#

Amortized analysis in algorithms is a method used to analyze the average time complexity of a sequence of operations on a data structure, particularly when individual operations can vary significantly in their time complexity. It focuses on understanding the average cost of operations over time, rather than the worst-case scenario for each operation in isolation.

In simple words, we can say that it’s a data structure analysis technique to distribute cost over many operations. An operation has amortized cost \(T(n)\) if \(k\) operations cost at most \(\leq k T(n)\).

“\(T(n)\) amortized” roughly means \(T(n)\) “on average” over many operations. Inserting into a dynamic array takes \( \Theta(1) \) amortized time.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) As an illustrative example, consider performing

insert_last()\( n \) times on an initially empty array. The resizing occurs when the array reaches capacities like \( 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, \ldots, n \), with each resize incurring a cost of \( \Theta(1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + \ldots + n) = \Theta\left(\sum_{i=0}^{\log n} 2^i\right) = \Theta(2^{\log n}) = \Theta(n) \).