Computing Time Complexity (Continue)#

Recursion Tree Method#

Before, we used the idea of a tree to determine the time complexity of an algorithm. Now, we will explore this method in more detail. The recursion tree method visualizes the recurrence as a tree, where each node represents a subproblem. By summing the costs of all nodes at each level of the tree, this method helps us understand the overall time complexity. It is especially useful for recurrences where the work done at each level forms a clear pattern, allowing for easy summation.

Example: \(T(n) = 3T(\lfloor n/4 \rfloor) + \Theta(n^2)\)

Let’s assume, as before, that the original problem size is a power of 2, so \( n/4 \) yields an integer. By looking at the schematic in figure \ref{}, we can see that at each level, we have three components, each dividing by 4 as indicated by \( 3T(n/4) \). At each level, we have a time complexity of \( \Theta(n^2) \). Note how the subproblem size decreases by a factor of 4 each time we go down one level. We eventually must reach a base condition.

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) How far from the root do we reach one?

We see that the subproblem for a node at depth \( i \) is \( \frac{n}{4^i} \). Thus, the subproblem size hits 1 when

Thus, we see that the height of this tree is \(\log_{4}{n}\) and its number of levels is given by \(\log_{4}{n} + 1\) (i.e., \(0, 1, 2, \cdots, \log_{4}{n} \rightarrow \text{depth } i\)). Note that the results obtained here are different from those of a binary tree.

Next, we determine the cost at each level of the tree. Each level has three times more nodes than the level above, so the number of nodes at depth \(i\) is \(3^i\). Because the subproblem size reduces by a factor of 4 for each level we go down from the root, each node at depth \(i\) (\(i = 0, 1, 2, \cdots, \log_{4}{n-1}\)) has a cost of

Next, we need to find the cost at each level considering all the nodes at each level. If we have \(3^i\) nodes at each level and each costs \( \Big( \frac{n}{4^i} \Big)^2 \), then

What about the last level? The bottom level at depth \(i = \log_{4}{n}\) has

Each node at the bottom level contributes \(T(1)\). Since \(T(1)\) is a constant time, we have \(\Theta(n^{\log_{4}{3}}) = T(1) \cdot n^{\log_{4}{3}}\).

Let’s now combine all the costs:

Where \(\sum^{\log_{4}{n-1}}_{i = 0}\Big( \frac{3}{16} \Big)^icn^2\) is the cost per level and \(\Theta(n^{\log_{4}{3}})\) is the cost of the bottom level.

We can solve this equation from two perspectives. We know that

and

Using the equation above, we have

which is quite a hard equation to solve. However, if we use the second equation, which requires us to assume that our sum extends to \(\infty\), we have

Finally, the time complexity is then given by \(T(n) = O(n^2)\).

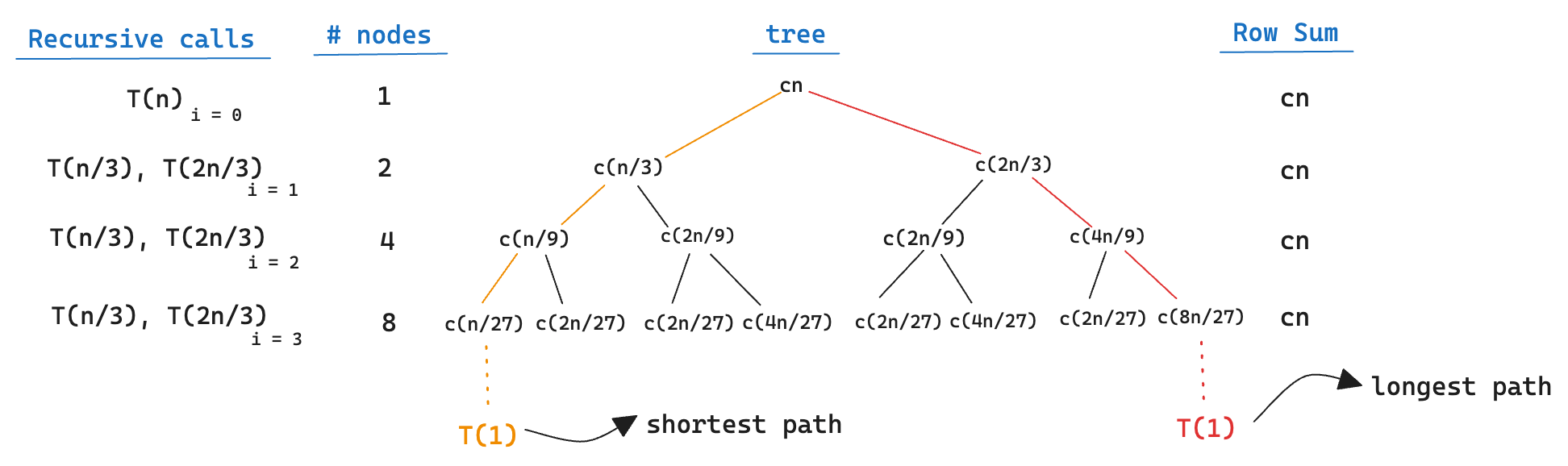

Example: \(T(n) = T(n/3) + T(2n/3) + O(n)\)

In order to find the height of the tree, let’s consider its longest path. At each level, we have \(\left( \frac{2}{3} \right)^i n\) subproblems when we look at the longest path. We’re interested in when this path is going to reach 1. Hence,

Then we have that \(i = \text{range}(0, \cdots, \log_{3/2}{n} - 1)\). Intuitively, we expect the solution to the recurrence to be at most the number of levels times the cost of each level. That is,

where \(\lg n = \log_{2} n\).

It’s important to note that each level contributes to a cost of \(cn\) up to a certain point. For instance, when the shortest path reaches a subproblem size of 1, it stops contributing to the total cost in subsequent levels.

If such a tree were to be a complete binary tree of height \(\log_{3/2}{n}\), there would be \(2^i\) leaves where at most \(2^{\log_{3/2}{n}} = n^{\log_{3/2}{2}}\) leaves. Since the total cost of each leaf is constant, the total cost of all leaves could be \(\Theta(n^{\log_{3/2}{2}})\). This recursion tree is not a complete binary tree; however, it has fewer than \(n^{\log_{3/2}{2}}\) leaves. To calculate the precise cost of the tree would take more effort. With that in mind, we can test our assumption of \(O(n \lg n)\) using the substitution method, which we shall introduce in the next session.

Substitution Method#

The substitution method involves making an educated guess about the form of the solution and then using mathematical induction to prove that the guess is correct. This method works well for many types of recurrences and is particularly useful when the solution can be easily guessed or when the recurrence has a known solution. Let’s see some examples:

Example: \(T(n) = T(n/3) + T(2n/3) + O(n)\) - from divide and conquer section

As we have seen before, this example is a bit hard to solve using only the tree method. With that in mind, let’s try to solve it using the substitution method. Let’s test our assumption that \(T(n) = O(n \lg n)\). Then,

Note, our assumption is that \(T(n) \leq d \cdot n \lg n\). Thus, we need to prove that \(- dn \lg 3 + \frac{2}{3}dn + cn < 0\), since we have obtained that

Hence, let’s verify that \(dn \lg 3 - \frac{2}{3}dn - cn > 0\)

Therefore, by mathematical induction \(T(n) \leq dn \lg n\) as long as the inequality \(d > \frac{c}{\lg 3 - \frac{2}{3}}\) is satisfied.

Reasoning Process#

I think it is easier to see what needs to be done with the substitution method when we convert the expression we want to prove into a negative format. For instance, our initial assumption is \(T(n) \leq d \cdot n \lg n\), and we obtained that

Thus, we need to check that there exists some \(\delta\) where \(T(n) \leq d \cdot n \lg n - \delta\). Because if our assumption is that \(T(n) \leq d \cdot n \lg n\), it follows that \(T(n) \leq d \cdot n \lg n - \delta\).

This \(\delta\) is the part of the equation that we need to prove is positive. From our previous steps, we found that

We just need to show that \(\delta > 0\).

Example: \(T(n) = 4T(\frac{n}{2}) + n\)

Our first hypothesis will be that \(T(n) = O(n^3)\). That is, \(T(n) \leq cn^3\). Thus,

In order for our hypothesis to be true, we need to rewrite the equation above using its negative form. That is,

Note how \(cn^3 - \Big( \frac{cn^3}{2} - n \Big) = \frac{cn^3}{2} + n\) which is the same we obtained in the equation above. We’re rewriting our equation for an easier understanding of what we should do. Proceeding with the analysis we have,

We see that for \(n \geq 1\) and \(c \geq 2\) we have \(\frac{cn^3}{2} - n \geq 0\). Therefore,

By mathematical induction, if the equation above is indeed true then we have that \(T(n) \leq cn^3\).

Even though our analysis until now is correct, we might be able to find some tighter function. Thus, let’s check if the hypothesis of \(T(n) = O(n^2)\) fits.

We want to show that \(T(n) \leq cn^2\). Thus,

Let’s now analyze the negative format of this equation. That is,

For the equation to hold, \(n\) would need to be a negative number, but \(n\) cannot be negative. Therefore, this equation doesn’t hold. Let’s then make a slight change to our hypothesis:

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) Remember: for time complexity analysis, we don’t consider the lower-order terms. Thus, \(O(n^2) = c_1 n^2 + c_2 n + c_3 n + \cdots + c_k n = c_1 n^2\)

Then, we have:

Let’s once again compute the negative part of the equation. That is,

To show that \(\delta > 0\), we have:

Therefore, \(c_1n^2 + c_2n - \delta \leq c_1n^2 + c_2n\) as long as \(\delta = -c_2n - n\) and \(c_2 \geq 1\). By mathematical induction:

Which proves that \(T(n) = O(n^2)\)

\(\textcolor{#FFC0D9}{\Longrightarrow}\) I recommend this Youtube video from for a more in-depth analysis on how to solve such equations video link.

Master Method#

The master method provides a straightforward way to solve recurrences of the form \(T(n) = aT\left(\frac{n}{b}\right) + f(n)\), where \(a \geq 1\) and \(b > 1\). This method compares the function \(f(n)\) to \(n^{\log_b a}\) and determines the time complexity based on this comparison. The master method is powerful for a wide range of recurrences, making it a commonly used tool in algorithm analysis.

Case 1: \(f(n) = O(n^c)\) where \(c < \log_b{a}\)

Case 2: \(f(n) = \Theta(n^c)\) where \(c = \log_b{a}\)

Case 3: \(f(n) = \Omega(n^c)\) where \(c > \log_b{a}\)

provided that \(af\left(\frac{n}{b}\right) \leq kf(n)\) for some \(k < 1\) and sufficiently large \(n\).

Example 1 Consider the recurrence:

Here, \(a = 2\), \(b = 2\), and \(f(n) = n\). We compare \(f(n)\) with \(n^{\log_b{a}}\):

Thus, \(f(n) = \Theta(n^1)\). By Case 2, we have:

Example 2 Consider the recurrence:

Here, \(a = 3\), \(b = 4\), and \(f(n) = n^2\). We compare \(f(n)\) with \(n^{\log_b{a}}\):

Since \(n^2 = \Omega(n^{\log_4{3}})\) and \(c > \log_4{3}\), by Case 3, we have:

provided that \(3\left(\frac{n}{4}\right)^2 \leq k n^2\) for some \(k < 1\) and sufficiently large \(n\).